Collaborative Intelligence: Distributed Metacognition and Simulated Conversations in Academic Literacy Events

In the 1940s when the first computers crawled out of the Industrial Age—computer scientists of the day called them “giant brains” both for their size and powers—the theme of AI-human competition arose in history. In the 1950s IBM scientists were fascinated with pitting computers against chess brainiacs. In 1985 a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon proposed a dissertation studying a chess playing machine which morphed into IBM project Deep Blue. By 1997 the media exploded with the news that Deep Blue had finally conquered a grand chess master in a nail biter series.

Competition between machines and humans is a big part of the fear and trembling rumbling around in the workplace and the classroom, not to mention law offices, banking institutions, and government agencies with their layers of bureaucracy. But at least in Australia a national agency is looking at the upside of collaboration. Paris and Reeson (2021) reported on new money flowing into a project called Collaborative Intelligence. AI-assisted chess players beat AI-alone and solo human grand chessmasters. AI-assisted humans beat AI-alone and human-alone. We are better together. Witness from their article:

“The most interesting question is not who will win, but what can people and AI achieve together? Combining both forms of intelligence can provide a better outcome than either can achieve alone.”

CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency, has embraced the theme of collaboration between AI and humans and is actively applying AI to intractable human problems like aligning education and training opportunities for indigenous people with the projected needs of employers, which requires knowledge of subjective local and regional motivations for a better goodness of fit. This application of AI tools with conversational capabilities could benefit education from kindergarten through the university. Witness:

Paris and Reeson (2021) wrote about their own CSIRO-funded project intended to better understand the conditions under which AI-human collaborations are most effective. For example, they cite the collapse of a building in Surfside, Florida, where robots were used to search the wreckage for survivors. As we have seen with ChatGPT, much of the quality of the output of the bot is determined by the parameters set in the opening prompt establishing the links among human, machine, task, and goals. The same principle applies to a robot embarking on a rescue mission in an ill-defined context. What are the most successful ways of building a robot-human thinking-doing team? As researchers Paris and Reeson operate under the following assumptions:

Educators face an additional layer of collaborative complexity when sociocultural dimensions of classrooms as activity settings with academic requirements, norms of participation including ownership of ideas, deeply entrenched individual models of learning with individual objectives, long-standing structures grounded in competition, and a dominant view of knowledge as acquisition of information and its attendant reliance on a transmission model of pedagogy are considered.

In classrooms actively pursuing collaborative intelligence between simulated cognition and human consciousness as a learning outcome, collaboration writ large becomes much more salient as a pedagogical planning and assessment focus. Indeed, research in secondary mathematics pedagogy is laser focused on understanding ways to teach using collaborative problem-solving small groups in settings that produce equitable opportunities to participate with agency and intentionality. They already use calculators. Simulated conversation is a short step away.

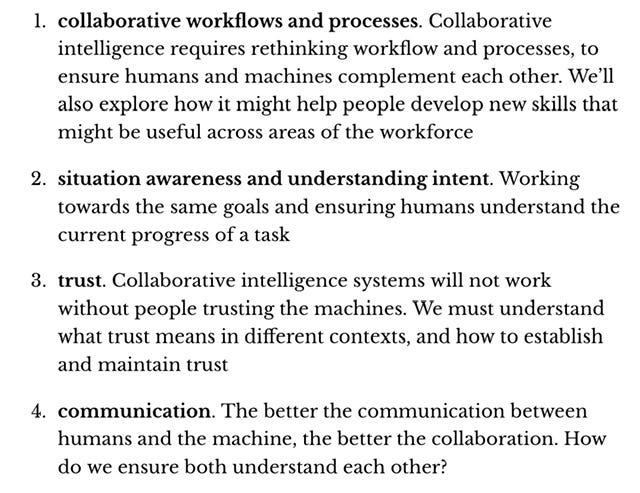

The alternative, defending against AI’s intrusion into human cognition, has been well researched and reinforced. I am reminded of Chester Finn’s objection to the use of computer assists for readers to build essential prior knowledge before reading a test passage on the NAEP. Why should a reader not be expected to know what a yacht is, say, and wouldn’t it be cheating to give the reader an informational assist? How would we know how well they could read if they ever find themselves stranded on a desert island? The exam in Foucault’s world where individual consequences befall individual acts requires a complete intellectual break from external affordances, and educators have plenty of technology to trap cheaters. Witness:

Clearly, individual competence for program completion or licensure must be heavily invested in assuring individual performances. But just as clearly, human learning is a social, cultural, historical process dependent on participation with others in collaboration working toward shared goals. What good would rescue robots have done in Surfside, Florida, if they were competing with the humans?