It’s understandable that the norm is to view language as an immutable object or a machine with a structure and a set of rules governing its moving parts. Mastering a functioning linguistic machine has been a primary objective of schooling from ancient times and remains so today. Parts of speech, affixes and suffixes, prepositions, formations based on case, number, tense and gender—structure and rules are crucial aspect of any effective and efficient signal system. The complexities of any system of human language demand conventions and social agreements.

But language is far more than a machine. It is a bond that builds between and among people in communities beginning with nuclear clusters we, using the English machine, term ‘families’ and extending into an institutional space we call ‘citizens.’ As Foucault revealed, language codifies power, knowledge, and truth, serving as a tool of a holy savior, a diagnosis of insanity, a legal decision to execute, a guillotine.

Because the interests and affairs of politically sovereign states intersect and overlap, linguistic communities historically have developed designated languages to be the lingua franca, a bridge language that affords the opportunity to communicate among speakers who don’t share the same mother tongue. The term originates from the Mediterranean Lingua Franca, a mixed language composed of Italian with a broad infusion of words from French, Greek, Arabic, Portuguese, and Spanish. Traders in the Mediterranean basin from the Middle Ages to the 19th century used this machine to great advantage. English is currently considered the global lingua franca.

The rise of the English language to the status of a global lingua franca began in the fifth century. The period called Old English (5th to 11th centuries) began with the arrival of Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons) and the Jutes from Denmark in what is now England and southern Scotland. Their languages merged with the local Celtic languages to produce a hodgepodge of complexity. Old English had a wicked grammar system. Nouns had one of three grammatical genders, and there were four cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative) used for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives. Verbs were conjugated as "strong" (forming past tenses by vowel changes) or "weak" (forming past tenses with a -d or -t suffix).

Old English vocabulary initially had a limited array of Latin loanwords, primarily related to Christianity and Roman civilization. Over time, especially after the Viking invasions, Old Norse words entered the language, leading to considerable lexical growth. Word order was more flexible in Old English due to the inflected nature of the language, allowing for variations that would be ungrammatical in Modern English.

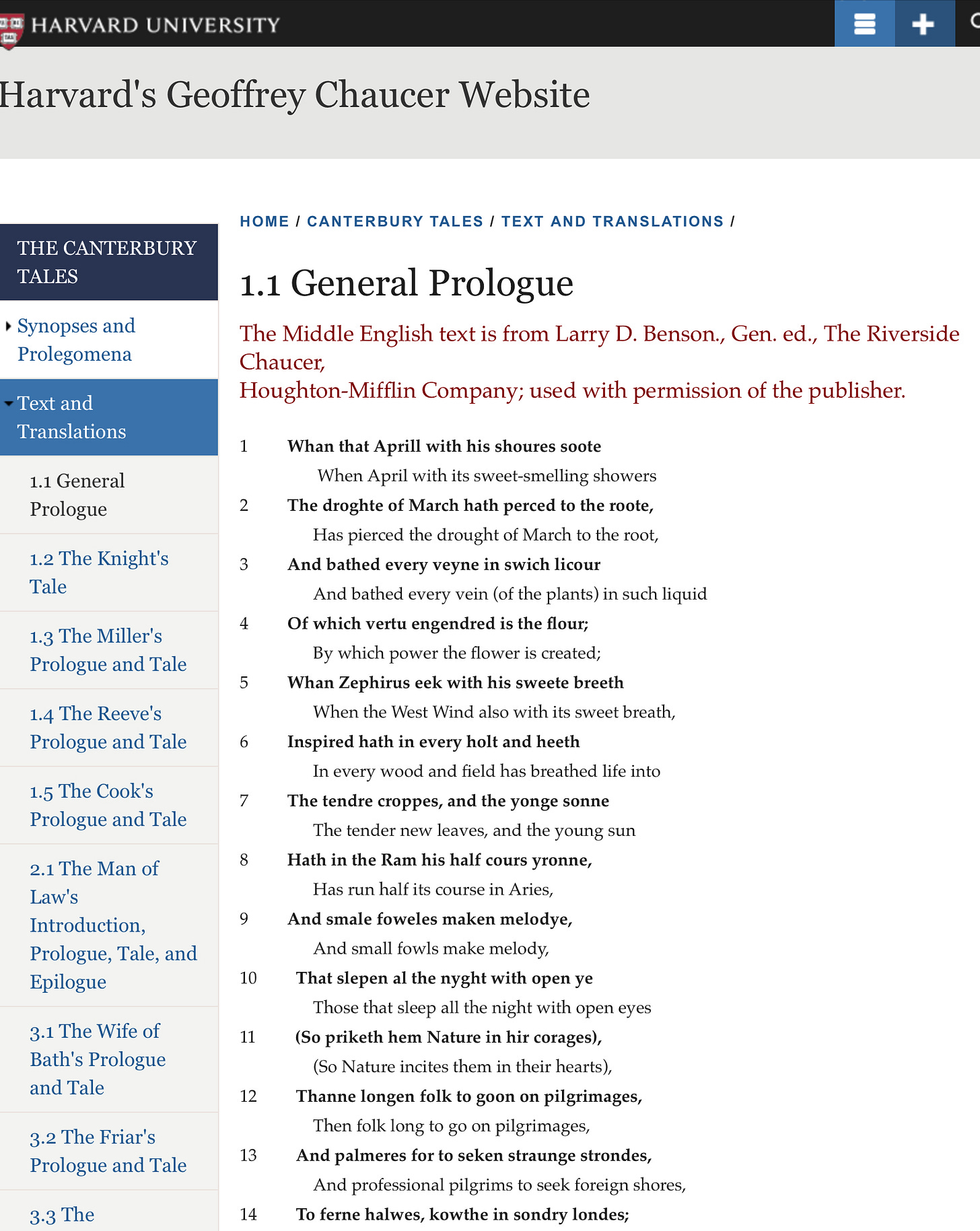

Just as the English language was born as the fruit of an invasion of tribes, its second period of development followed the Norman Conquest in 1066. Political violence may be among the most potent forces shaping deep linguistic change. The period of Middle English (12th to 15th centuries) experienced a mixing of French and some Latin with Old English. Without systematic instruction, reading texts written in Old English is impossible. Middle English is doable with the help of a glossary. Here is a screenshot of some Chaucer:

The Renaissance contributed to substantial growth in English vocabulary through the absorption of Latin and Greek words. The establishment of the first English printing press by William Caxton in 1476 also standardized English spelling and grammar to a certain extent. The expansion of the British Empire across the globe spread the English language through colonization, and English was adopted as the language of administration and elite social segments in many countries. With Britain at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution, English became the language of industrial and technological advancement.

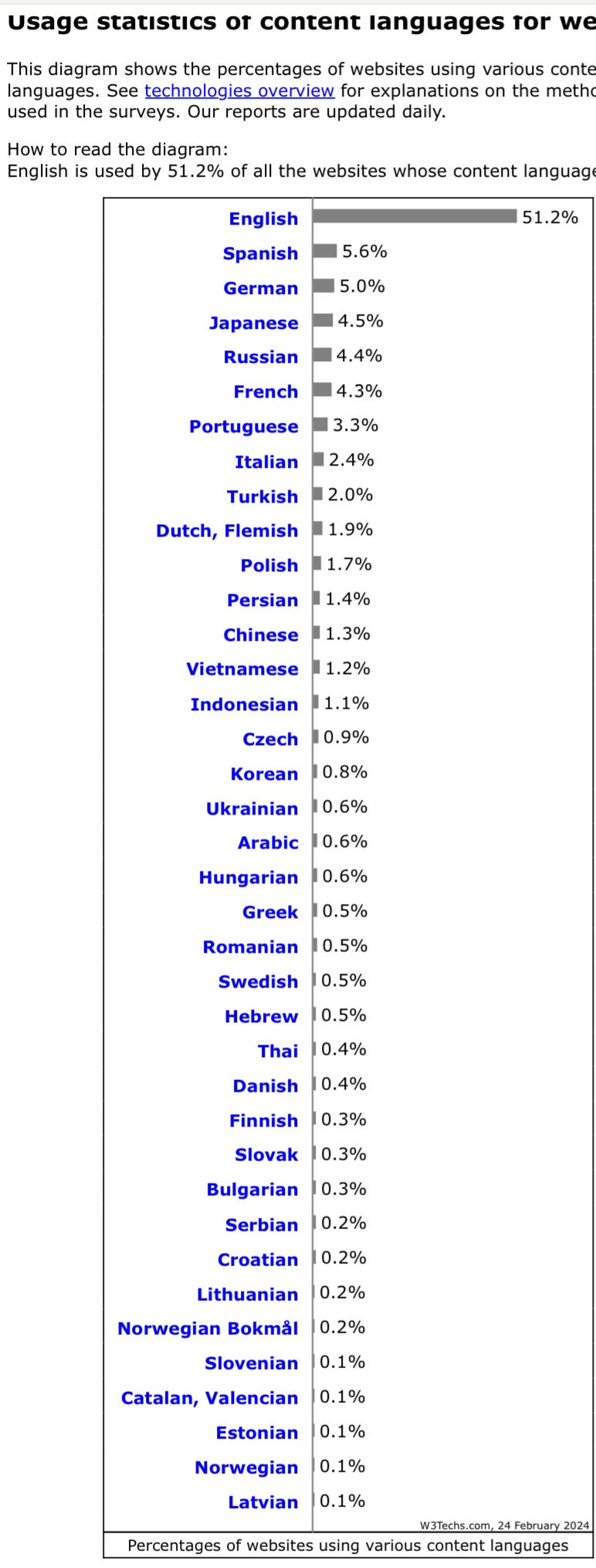

The economic and cultural influence of the United States, particularly after World War II, further solidified English as a global language. The domination of the American entertainment industry and the spread of American-style capitalism increased the reach of English. Globalization and the Internet have by default made English the primary language of international business, diplomacy, science, technology, and aviation. It dominates the digital landscape, with the majority of content on the Internet in English.

*****

Plato decided that the origin of words lies outside the ken of mortals, divining that “names belong to things by nature”; moreover, “the artisan of words” qualifies for the role by “keep[ing] in view the name which by nature belongs to each particular thing.” The task of the artisan, therefore, is to observe and to listen to the wind, the rocks, the horses, to each particular thing, to ensnare its name.1

The robed Philosopher strolled through the vibrant agora in a thriving Greek metropolis. The air smelled fresh from the sea breezes. As he gazed at the surroundings and observed flourishing vines, he heard whispers of ‘vineyard…vineyard…vineyard.’ Included in the view, a gift from the gods, he could see a bowing figure arising from the soil. ‘Olive tree, olive tree, olive tree,’ the figure sang. ‘Harmony, harmony, harmony,’ a chorus of olive trees sang, reminding him of last nights futuristic dream of attending a concert by The Beach Boys.

Epicurus believed in a way oddly complementary to Plato that words arose naturally. Primitive utterances would have been spontaneous and instinctive reactions to the surroundings. Most of Epicurus’s writings have been lost, but quotations and ideas attributed to him have been influential. Of course, in the 21st century, an epicurean is a culinary snob with a taste for fine food and expensive wine.

Epicurus was often misunderstood after the shellacking he took when Christianity branded him a materialistic hedonist despite his work being unavailable to defend himself. He believed in a simple life of sharing, but he didn’t believe in the gods. Epicureans valued communal living and community where individuals supported each other's pursuit of happiness.

In fact, he purchased a plot of land in Athens where he hosted his school he named “The Garden." I’m not sure if this is the garden we have to get back to or if it’s the other garden in the Crosby, Stills, and Nash song, an example of double vision on words. It was an inclusive community where men, women, and even slaves were welcomed to study and discuss philosophy. It’s only natural the Epicurus would conclude that words came naturally from observing and listening to things, especially from watching and listening to one another.

To a dimly lit cave, thick with the scent of soil and the musk of animal hides, a Homo habilis man, his brow knotted, skin glazed with the sheen of sweat, returns empty handed to the hearth, flames casting dancing shadows on the cave’s walls. His mate, her hair the tangled roots of blackberry bushes, sits cross-legged on the ground, grinding seeds between two stones.

The man's gait is heavy. Each footfall thumps on the packed earth. He pauses, furrows creasing his brow, crow’s feet at the corners of his squinting eyes, his hands clutching his temples. A desperate grunt, low and guttural, resonates in the dusky mustiness.

His mate lifts her head, her sharp gaze registering his pained expression. She tilts her head, her own grunt an inquisitive one, a soft, questioning lilt at the end of the utterance. He hisses through clenched teeth. His fingers massages his temple in slow, circular motions. She nods in understanding with a sibilant whisper. With the quiet grace of a hunting cat, she approaches him and massages his back.

How could she tell him that she was happy that he had a headache? She had been planning to feign a headache upon his return at the first signs of friskiness.

The fact is there is no scientific consensus on the origin of language. Though much is known through scientific study of the origins of the human species, important questions about language remain unanswered. In a way, this uncertainty is a good thing; it frees us to speculate. As others have noted, if we got language from a cave man with a headache moaning and gnashing his teeth, why don’t chimpanzees, smart creatures themselves, who also hoot and holler and bellow, not have language?

In 1866 the French Academy banned papers on the origin of language because their scholastic system was overwhelmed with speculative submissions. Perhaps the Academy was not eager to gain a reputation for publishing fiction.

*****

Human beings are notoriously imperfect artisans of words, however, just as Plato wrote, and they must re-discover or re-create nature’s words with every utterance, one eye on the world, one eye on the word, double vision, missing the mark most of the time.

While Plato’s scenario of the whispers of things announcing their names was accepted as plausible during Plato’s time, it is worth noting that names for things in the natural world have come and gone over the centuries, realigning themselves with new meanings as well as having children. In ancient times, observing the world for new particular things was salient, and listening for newly seen things to announce their names was a curious necessity. They had no names for so many things because so many things had gone unnoticed in the folds of time. It’s no exaggeration to say that probably every square inch of Earth has been seen and named by now. Yet still we see freshly and find new names or rearrange old ones.

An early 20th century analysis of the origin of the 1,000 most frequently used words in Modern English uncovered 61% from Old English and 31% from Old and Middle French, a motley linguistic heartland (cited in Robertson and Cassidy, 1954)2. This analysis was based on Thorndike’s list of high frequency words and on Ernest Horn’s A Basic Writing Vocabulary. Among the 250 most frequently used words in English are one-syllable borrowings from the French: just, place, part, use, city, large, line, state, sure, change, close, coarse, fine, pay, please.

From the Norman French even before the Norman Conquest, English gets cattle and catch; a few centuries later come floods of words from the more prestigious Parisian French where English pilfered chattel and chase. Regal, real, and royal arrived in triplets through streams of Latin and French during the medieval period as did legal, leal, and loyal. The acquisition of a French word didn’t mean the loss of an English word. We have table and board, labor and work, chair as well as stool. English has the humble ox, cow, calf, sheep, swine, and deer; it also has the French swanky beef, veal, mutton, pork, bacon, and venison. Who among us eats pig or cow or sheep—unless the pig is barbecued buried in a pit.

Words in all living languages can change their meanings over time. The verb go, for example, meant “to walk” in Old English. “I am going to the forest” meant “I am walking to the forest.” In modern English going somewhere means anything from flying in a Boeing 757 to heading for stardom. In Latin virtue meant “manliness” generally and then specialized to mean “warlike prowess.” If you revisit the snippet from Chaucer above, you’ll find the word “vertu” glossed as “power.”

When virtue was borrowed from French into English during the Middle Ages the meaning changed from the Latin “manliness” and military power to power more generally or “magical power” as in Milton’s “virtuous ring and glass.” Virtuous as in chaste is modern; neither the ring nor the glass are relevant to virginity.

The “ring and glass” Milton alluded to dates back to Chaucer’s “The Squire’s Tale.” The son of the Knight, who tells his own courtly tale of love, chivalry, fate, and divine intervention celebrating the noble ideals of the knightly class, the Squire narrates a surreal tale of two suitors in competition for the same woman. The arrival in the Squire’s tale of a mysterious knight on a horse made of brass twists the courtly genre a bit.

The knight bears a sword, a mirror, and a ring, which he presents as gifts to the king. His brass horse can travel vast distances in a short time; the sword can pierce any armor and heal the wounds it makes; the mirror can reveal friend from foe and foretell future events; and the ring enables the wearer to understand the language of birds and the medicinal properties of plants.

The focus then shifts to Canacee, the king’s daughter and the object of dueling lovers, and the magic ring. The following morning, she wakes to the singing of a distraught female falcon, whom the ring helps her understand. Canacee learns of the falcon's woes from her sorrowful tale of being betrayed by her mate for another. Canacee comforts the bird and takes it under her care.

The tale breaks off and Chaucer moves to a different topic. Readers never learn what becomes of the other gifts, of the quest for love, or of a significant upcoming tournament. Why Chaucer left "The Squire's Tale" unfinished remains a topic of speculation. Some suggest that the tale's structural complexity and grand scope may have been too ambitious, or it could imply thematic meanings about the nature of storytelling or the squire's character. Critics comment on the tale's dreamlike quality, the contrast between the ideals of courtly love and the harsh reality of the world, and on the exploration of human and animal emotions.

Several centuries later, John Milton connects the ring and glass to virtue which, you recall, originated in the ancient world to index power, especially manly power, especially violent and physical power. In the poem “Il Penseroso,” Milton celebrates the isolation and melancholy that can engulf the more scholarly inclined who spend their lives poring over complex literature accompanied by “the cherub Contemplation” and “the mute Silence.” In the following lines Milton reached through time to find Chaucer speaking to him about the virtues of a girl speaking with birds:

“Or call up him that left half told

The story of Cambuscan bold,

Of Camball, and of Algarsife,

And who had Canace to wife,

That own’d the virtuous ring and glass,

And of the wond’rous horse of brass,

On which the Tartar king did ride;

And if aught else, great bards beside,

In sage and solemn tunes have sung,

Of tourneys and of trophies hung,

Of forests, and enchantments drear,

Where more is meant than meets the ear.”

Virtue is a heavy-duty word which has passed through a plethora of semantic filters as it traveled to the 21st century, and there are others like it. Injury was limited to an “injustice” in earlier times but has expanded to encompass accidental destruction or damage to one’s psyche, body, to a tree, to the ocean, and companion meant “one who shares bread with you” who today can also share a bed with you. Undertaker once meant “one who undertakes something”; reek meant “smoke,” not “a foul odor.” Liquor was a synonym for any liquid (see Chaucer again), and corn meant “wheat” in England, “oats” in Scotland, and “maize” in America. Pipe took on a variety of meanings in the minds of smokers, plumbers, and organists. Girl meant “young person of either sex.”

English words have been elevated and degraded in various periods. Lust meant “pleasure” in a general sense, lewd meant “ignorant, unlearned,” knave or imp meant “boy,” and hussy meant “housewife.” In the seventeenth century the word bard was a term of contempt roughly equivalent to vagabond. Tory, Whig, Puritan, Quaker, and Methodist were all at one time terms of contempt, and a minstrel was a juggler or a buffoon before becoming a musician. Nice was used to mean “ignorant” very early on, moved through French to mean “foolish” and came to rest in Modern English as a sort of catch all for the opposite of “not nice.”

My favorite fickleness is the euphemism. Die now means to pass, to expire, to succumb, to depart—anything but to croak or kick the bucket—and the dead person is the lost, the departed, the deceased. Cemetery was once a euphemism (literally, a “sleeping place”) but the word has been so closely associated with a burial ground that we have new euphemisms like “memorial park.” A cretin at one time was a dialectical variant of a French word meaning a “Christian,” far distant from its current meaning of “moron” or “mentally deficient.”

**

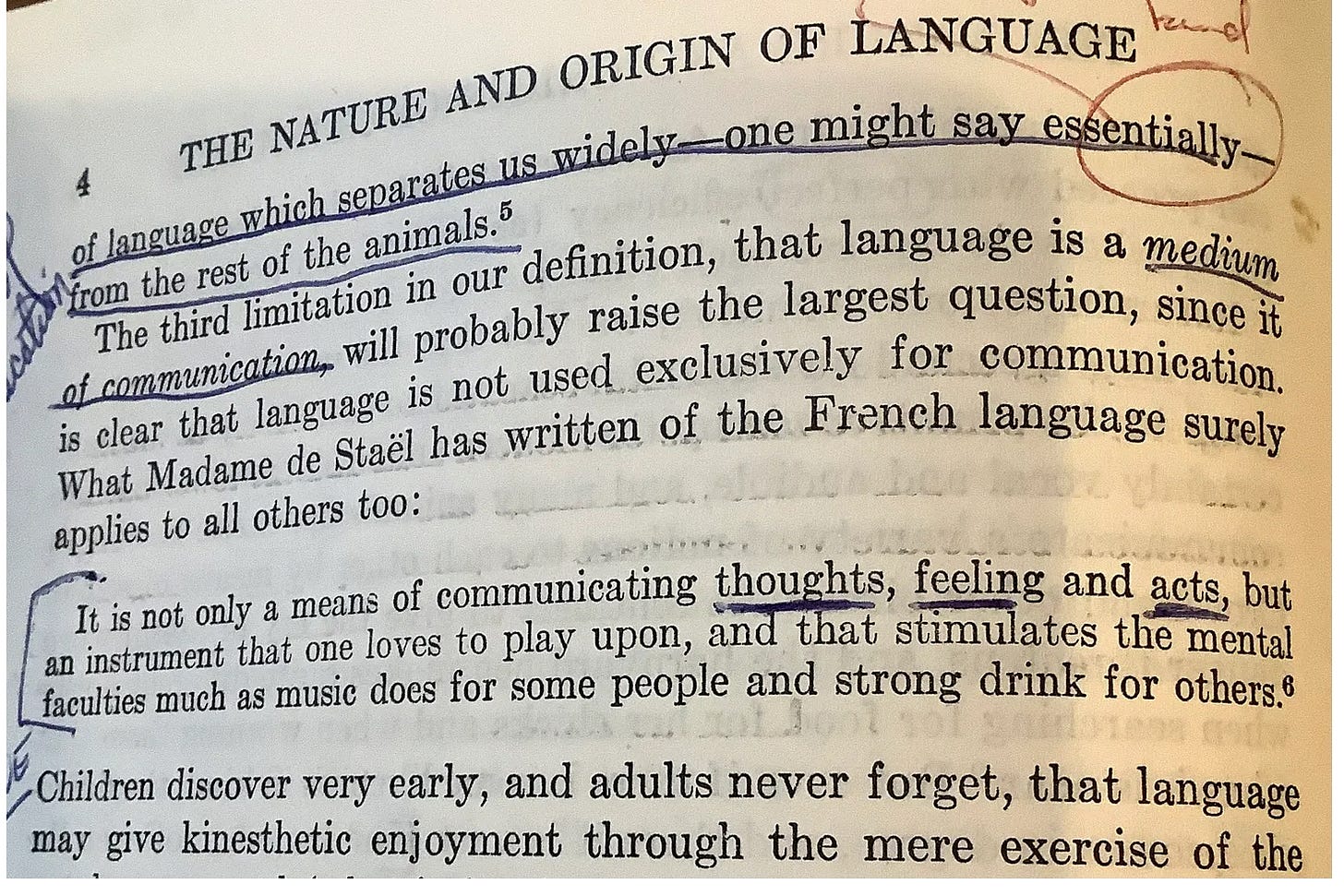

As Bahktin continuously reminds me, language belongs to everyone and to no one. Schooling insists that children study phonics, grammar, spelling, vocabulary, sentence structure—everything about language as a machine used to communicate my intentions to you. Perhaps a more realistic, historically informed perspective on language could help close the achievement gap. Language is anything but fixed and stable. In their staid, scholarly textbook fit for the pensives enthralled by language as Milton describes in his poem reaching back to the young Squire through the living mind of Chaucer, Roberts and Cassidy (1954) in my fifty year old textbook admit to taking a strict school view on language as communication, but they acknowledge how much they leave out:

Roberson and Cassidy (1934, 1938, 1954). The Development of Modern English (2nd edition). Prentice-Hall, Inc.

The remainder of this discussion relies heavily on Robertson and Cassidy (1954), the textbook we used in the course “Growth and Structure of the English Language“ I took as an undergraduate and from my notes from the class.