An Afternoon with George Washington

Driving to the prison, you could hear banging, howling, and screaming half mile away, a cacophony reverberating through hallways and out barred windows open to let in the evening breeze. It put me in mind of Maurice Sendak and the Wild Things.

Towers with machine guns and strands of barbed wire atop a high metal fence safeguarded the long rectangular building with its many wings branching off. The parking lot was jam packed.

The State Department of Corrections employed a small army of law enforcement and medical professionals budgeted to the custody and care of a criminal element with medical and psychiatric needs not enough for a rubber room yet dangerous enough to segregate from the normal criminal population across California. Vacaville was called the ‘country club’ by convicts because inmates were prescribed psychotropic drugs.

*

Inside the building, you passed through sally ports until you reached your destination wing. My routine destination was the R-Wing, Education, where I taught an evening course in Freshman Composition through a collaboration between Solano Community College and the Department of Corrections.

A small fraction of convicts had earned diplomas and degrees in the real world and were beyond the scope of remedial, vocational, and GED programs, the bulk of the work of R-Wing. Many of my composition students, though not all, were good writers, having written extensively about legal matters, petitions for parole, pleas for outside supporters of parole. One had owned five automobile dealerships. Some had published articles in respected newspapers and chapters in books. One was later paroled and became a lecturer at UC Berkeley.

*

On this particular day, December 27, 1984, W-Wing was my destination.

W was the lock-up wing for the complex, a prison within a prison, the isolation wing, where criminals who commit crimes against guards or inmates spend their days—sort of like on-campus suspension in middle schools without a bell at the end of the day.

George Washington, a transfer inmate from Folsom to California Medical Facility at Vacaville, had agreed to do an interview with me arranged by the R-Wing administrator, Fred, my supervisor. Before the scheduled date, George had assaulted another inmate and was put in the hole, complicating but not short-circuiting my access to him.

In California in 1984, convicts in state prison chose between work programs or rehabilitation/education. I was reminded of the choice between vocational training and the college curriculum in high school. Guess what most chose?

*

Even time off your sentence for choosing education couldn’t compete with pay and apprenticeship. Fred explained the lure of work as the predictable outcome of educational trauma in childhood.

Most inmates he saw were inner-city black male high school dropouts who had gotten a bad taste of education. For them, education had been a nightmare at worst; at best, school had failed them. Still, he persevered.

Fred was firm in his belief in rehabilitation grounded in his hope for a better future. I think of Fred as a good and decent man doing a demanding job with the wisdom to keep his eyes on the prize—reducing recidivism. He was a mentor for me on R-Wing.

*

He was interested in my request to do this interview with Washington, first, because Washington volunteered to talk with me. Nobody else in the remedial reading classes raised a hand when the teacher put out the request. He had expected to have to choose one.

Second, Fred had no idea what George might say. He wanted to know. He had not discussed learning to read with any of them, though the remedial classes were the biggest.

Third, if it worked out, Fred might use George’s story in the education newsletter he published for the inmates. Unfortunately, I have no copies of these documents, an absence in my filing cabinet missed over time. I did collect copies of newsletters when I interviewed adult reading students at the Napa Public Library

Later, when I taught middle school, I worked for Bill Giachino, the principal of James Rutter Middle School in Elk Grove; when I worked as a writing instructional demonstration teacher in the elementary schools in the same district, I worked for Pacita Fagaragandean, principal at Markofer Elementary. Taken together, Fred, Bill, and Pacita came to serve as a touchstone for me, exemplars of the type of administrator public education needs, those with a profound sense of mission and a wise, wide ranging, pragmatic interest in qualitative data.

*

George’s remedial reading teacher, a Department of Corrections employee, reported to Fred that George had worked hard with his reading and writing since his transfer from Folsom.

She was disappointed that he’d blown a gasket and found his way back to the hole again, the second time since his transfer, this time for assault with a deadly weapon on another inmate.

She was surprised he was willing to talk.

*

I waited at the gate to W Wing. Fred appeared and entered the lock-up unit. We greeted the sergeant of the lock-up, signed a register, and waited in a small, barren office for a guard to bring George from the hole.

George was handcuffed. I paused awkwardly when the guard asked me whether to take them off. Fred intervened with something about an abundance of caution. He produced a paper for George to sign, a document releasing Corrections from any responsibility for the interview.

“It just means that you’re going to take full responsibility for what you do with him,” he explained. “You’re not going to blame the Department of Corrections. We’re not—I’m not forcing you. If you really should say ‘No, I’m not going to get involved,’ you can go back to your cell. And I mean that. I want you to be completely free.”

George said that he had volunteered. He was here. Fred called for the guard to free George’s left hand, the convict signed the release, the guard secured the cuff again around his wrist, and we were off to the races.

*

George was born in 1955 in Phoenix, Arizona. Barry Goldwater was an elected member of the city council at the time. In accordance with changes to the state constitution consonant with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the Phoenix schools were desegregated the year he was born.

He remembered nothing substantive of those years. But he did have a vague memory of going to a preschool or a daycare for a short time. He never went to public school there, he was too young before his family moved, but he didn’t think the schools were any good. He had four older siblings in the Phoenix public schools, and he knew for a fact that none of them could read well.

“None of my brothers can’t read,” he said. “My sister… vaguely. My father, he can read, he does maintenance work, and his hobby is customizing cars. My mother, she can read, she work for Thrifties. They, you know, lived together, you know what I’m saying? You know, they live together today. I never got any confusion from my mother or my father.”

*

The family moved to California, in 1959 when George was four. He started first grade at Lincoln Elementary School, which was open in 1984 but closed its doors in 2018.

George’s family moved to the city of Compton during a transition period when white people were moving out while black people were moving in. In 2021 NPR interviewed individuals who were living in Compton when the change in skin color of home owners occurred almost overnight1.

*

George recalled two experiences during his primary grades with significance in the timeline of his personal history as he recounted it to me. I chalked them up as evidence for Fred’s argument about educational trauma.

“Sometimes my first grade teacher had me read to the class,” he said. “I remember one time I pushed a boy down, ok, and he hurt his back, and I got suspended for that. I pushed him down because he was laughing at me because I couldn’t read good. I got a whuppin for that from my mother and my father. That’s the only time I ever got a whuppin from them.”

He remembered getting whuppins in school during first grade—“whuppins… or swattins. I don’t know why. I guess I just wanted attention. Then after they found out I wasn’t progressing, they put me in a special trainin’ class. I remember when I was in the second grade, I used to have to go somewhere with my mother to a place where a man used to try to teach me to read.”

Lincoln Elementary closed its doors a few years before COVID assaulted our way of life, our healthcare system and our public schools. The following screen shot reports on the vital statistics of the school during its final academic cycle2:

*

George remembered few specific details between grade school and high school. “I wasn’t in no special class in junior high,” he said. “I don’t know how I passed. I just passed. We took tests, and I was making F’s, but they passed me anyway.”

At some point he ducked out of school and returned when he was 15. “That’s when they, see, I was going to the regular classrooms until they found out I wasn’t doin’ nothin’ and, you know, they put me through another test and they put me back in the special trainin’ class. That went on ‘til I just quit.”

George completed his junior year of high school. “After that summer, I never went back to the twelfth grade. I don’t know how I made it that far. They was just, I don’t know, they was just putting me in grades. I wasn’t doing nothing. I seed I wasn’t goin’ no where in it, and plus I had a wife, not a wife but a girlfriend. She was pregnant and I wanted to support the baby so I quit.”

*

Before his appointment with induction into the California prison system in September, 1983, when he reported to the reception center at Chino to be assessed for placement, George had found productive work. He poked around at odd jobs for a time until Laureen, a woman married to his friend, took him to the city’s personnel office and filled out an application for him.

“She work for the city,” he said. “And I got a job trimmin’ trees for the city, tree trimmin’ trees, ok, I had to drive my own truck around, right, but I couldn’t go no where. I couldn’t—I didn’t know the streets. I could be right there at the street and even if I see the sign I still wouldn’t know. You see what I’m saying? I was lost.”

George lost his job trimming trees, but he stumbled onto a government funded program for blacks to learn to weld. “It was for blacks. It was a special…aw, I forget what they called it. They don’t have it no more. They pay you to go to school. I went through all the trainin’ but I couldn’t pass the test because I couldn’t read it.

“I tried, but there was just too many big words. I didn’t know how to do nothin’. I learned how to weld, but what good would that do you if you couldn’t read? You might have instructions, you know, you might have to read something. If you can’t read, winds up you don’t know how to do it.”

George felt that if he’d gotten a welder’s license he might have bypassed prison. “If I had gotten my license, I probably would have been a lot happier. But I didn’t pass. I just went and found a job where they just accepted you the way you was. It was just a job weldin’ pipes and stuff on cars. It lasted about six months ‘til the guy had to close his shop.”

As part of my ongoing project interviewing adult literacy student, I had read about the birth of standardized reading tests as tools to sort soldiers fighting in the two World Wars by reading ability. Instruction manuals for repairs and maintenance of complex machinery demanded individuals skilled at varying levels. Reading was a matter of national security.

George was aware that his dad, who worked on cars, relied on manuals and could read them. He should have worked harder in school. He felt considerable shame because his mother and father had spent all of their money on lawyers.

I wondered how George and his siblings had fallen through the cracks of standardized testing in public schools. George had fathered eight children that he knew of. He didn’t know anything about them.

*

His reception at Chino ended with his initial placement at Folsom, one of two California prisons reserved for murderers, where he stayed for a year. For reasons unclear to me, he was transferred to Vacaville where he spent a few spans of time in the hole in W-Wing by the time I met with him.

“I know… I thought about everything,” he told me near the end of our talk. “I’m in this prison because I don’t know how to read. The first thing… I didn’t want nobody else to know about it, right? Anywhere. Ok. I tried to hide that, and it’s hard to hide, and it caused me to start drinkin’ to hide it, to hide the truth—from myself. I was drivin’ myself. And, uh…

“I just started getting violent. But I been a violent person all my life. Drinkin’ just makes it worse. I’m an alcoholic. Goes back to school, goes back to drunk drivin’, goes back to a whole lot of stuff. Goes back to hurtin’ my best friend—that’s why I’m in here. Goes back to hurtin’ another guy in here, and that’s why I’m in here [in the hole].”

George Washington argued that almost all of the inmates he had encounters with are weak readers and worse writers. He also argued that life on the street was hard without literacy.

“I can’t read the help wanted ads,” he said. “I can’t do a job application. I had to cheat to get a driver’s license, send in somebody to take the test and then switch to take the picture. I couldn’t even have a bank book. I go into a bank with a lot of money, I hand it to a guy and trust him? I’m not gonna do that. When you can’t read, there’s a lot of things you have to trust. And I don’t trust people.”

George had words of advice for other inmates. “If you don’t learn to read, then it’s as simple as that, half of ‘em at least is coming back—for robbery, for burglary, sellin’ weed, whatever. If you can’t read and write and make it out on the streets you gonna do wrong. You gonna go out there and sell cocaine and sell some, uh, and make them women sell they pussies you see what I’m sayin’—you gonna do something. I ain’t gonna go out there and starve.”

*

Over the years I’ve returned to George’s interview several times just trying to understand. ‘I got a tree trimmin’ job for the city, trimmin’ trees,’ has played in my mind like a line from a Bob Dylan song. Then the street signs with indecipherable names and the ‘I was lost.’ It is haunting to think that he may still be hearing the cacophony of the Wild Things every night in his cell as I write almost forty years later.

From my vantage point in 2022, this interview clarified for me the power of ideology as a set of values and beliefs about what the world is, what the world can be, and what the world should be, that motivates action. In human affairs ideology is as often fueled by irrational belief as by reasoned judgment.

True believers in an ideology, blind faith in an irrational model of the world, lead simplified lives in that they need not trouble themselves with building knowledge and thinking critically. The ideology of white supremacy, a peculiarly stubborn American ideology, frames a world that works based on racial differences. Simplified. Deciding how to vote requires no intellectual nor ethical reasoning for an ideologue.

*

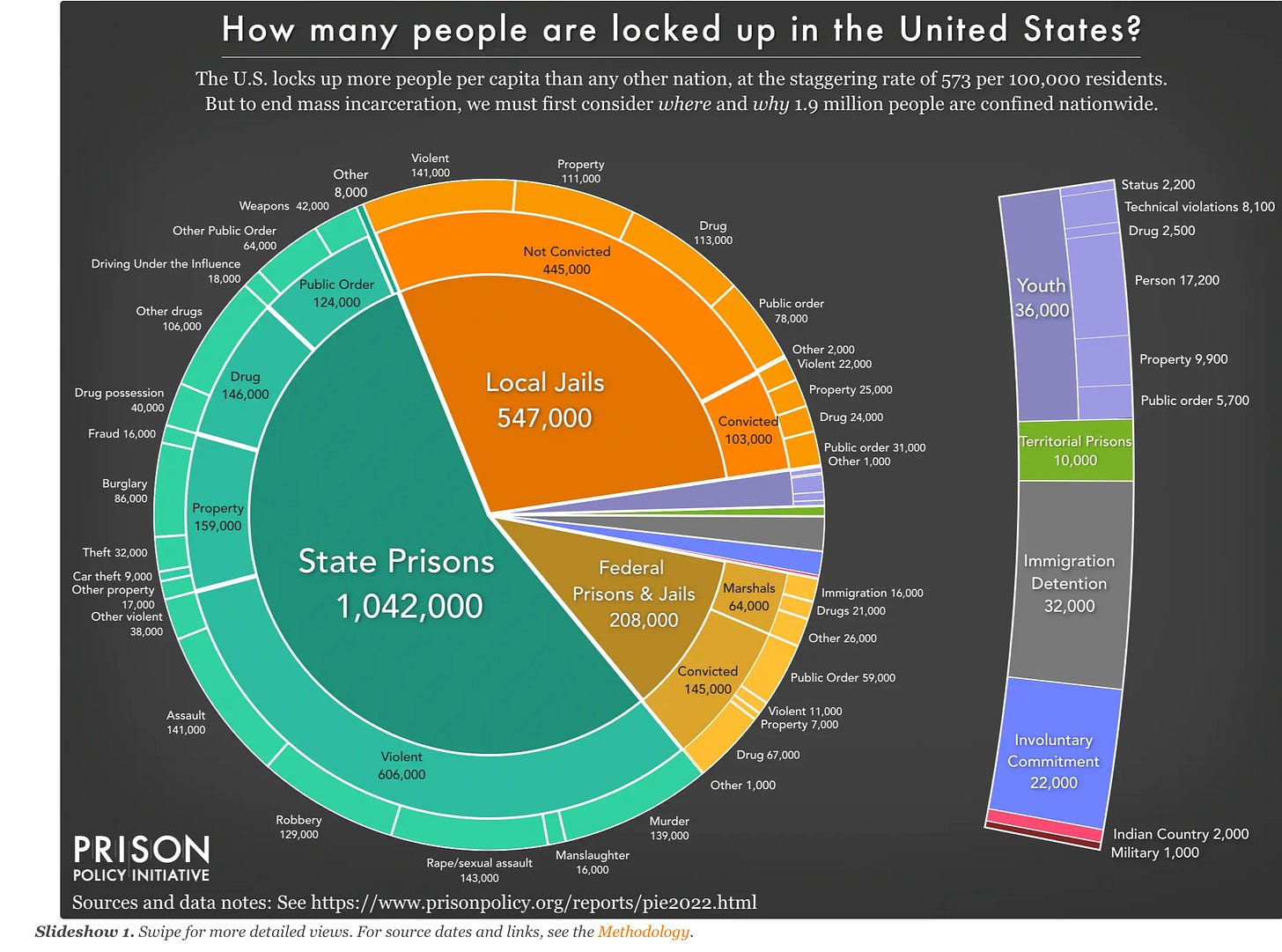

It is no accident that George is systematically produced and reproduced year after year in this country. It is no accident that our incarceration rate is so stunningly high, that disparities in incarceration rooted in sociocultural and racial differences are so easily tolerated. If punishment is certain, deterrence is fortified, and right society is gratified and secure.

These facts are outcomes of political ideology. This graphic represents the numbers generally. Visit the website for more information.

For George Washington school was a way station on the road to prison, a factory all but guaranteeing predefined outcomes from predictable inputs through scientific management of autonomous processes.

Scarce resources are budgeted ideologically to ensure they are effective in reaching students who are likely to succeed, not wasted on the long shots. The mission of efficiency in management is to serve the country through developing a proper work force.

School could be a place for emancipation and full participation in our democracy as members of local communities learn to think for themselves through pragmatic scientific management. The mission could to lay the foundation for self-actualization, critical thinking, and ethical reasoning and to change the trajectory for historically underserved learners.

*

Speaking of social science, Pierre Bourdieu, a French sociologist who gave us concepts like ‘cultural capital’ in an analysis of symbolic economies, took issue with Comte, a 19th century sociologist, who equated language and ‘wealth’ in a manner that objectifies language as a sort of jewelry or pleasure palace, ignoring the linguistic violence done against children like George Washington:

“‘Language forms a kind of wealth, which all can make use of at once without any diminution of the store, and which thus admits a complete community of enjoyment; for all, freely participating in the general treasure, unconsciously aid in its preservation.’” (A. Comte, System of Positive Polity, 4 volumes [London: Longmans Green and Co., 1875-1877], vol. 2, p. 213; quoted in Pierre Bourdieu Language and Symbolic Power, p. 32–see footnote 2 below)

As a type of wealth, however, the powers of language are not equitably distributed, and are not free in any economic or political sense. Community resources must be budgeted and managed to provide access to literacy as cultural practice. Not all people have access to the palace. Not all are admitted to a complete community of enjoyment.

For Bourdieu language as wealth becomes symbolic capital in a capitalist economy controlled by political capital. The power of language to issue a command and demand its fulfillment doesn’t come from grammar and syntax. Linguistic power to do violence or good to large numbers of people is accumulated by a small fraction of people and rationed to the rest, controlled by legislators with political capital.

“The concentration of political capital… [among] a small number of people…is prevented with great difficulty—and thus all the more likely to happen—the more completely ordinary individuals are divested of the material and cultural instruments necessary for them to participate actively in politics, that is, above all, leisure time and cultural capital” (p. 172).3

*

Elizabeth Hinton, a professor of history and law at Yale, published America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (2021), narrating the recurrent violence and death in black projects across the country beginning with the War on Crime in the sixties.

Police surveillance and militarized activity intensified and created volatile dynamics in black communities across the country during these years, resulting in armed rebellion. Over decades community activists worked to redirect control from the police departments back to community leaders with expanded resources for schools, jobs, and businesses. Police domination proliferated leading to George Floyd, the immediate antecedent event sparking the book.

Hinton documented a failure to disrupt white supremacist ideology motivating police aggression in urban areas and replacing it with a community reconstruction pragmatism. In her conclusion she pointed to the shrinking funding for Head Start, “the most visible remnant of the War on Poverty and a program that helps poorest children prepare for school” (p. 307). Overwhelming research points to the positive lasting impact of high-quality preschool on achievement in school.

I will end this post with a fact from Hinton: “The federal government spent about $2.7 billion on employment programs for low-income youth in 2020, while investing… $6.1 billion on grants and assistance to law enforcement” (p. 307).

https://www.npr.org/2021/05/05/993993572/how-a-predatory-real-estate-practice-changed-the-face-of-compton

https://www.publicschoolreview.com/lincoln-elementary-school-profile/90059

Bourdieu, Pierre (1999). Language and Symbolic Power. Harvard University Press.