Hemingway’s memoir titled A Moveable Feast was published in 1964, an impossible metaphysical distance from Paris in the 1920s, the substance of the work. His title by itself suggests a celebratory mode of writing apropos the setting. Whether in the Dingo Bar where Hemingway and Fitzgerald first met or in La Closerie des Lilas in Mont parnasse where Hemingway mentions he wrote parts of The Sun Also Rises, the feast he means had to be first “moved” through rich and complex memories forty years old. This resurrection of long quiescent experience resurrected Hemingway himself for a brief moment.

Think of it. EH. Forty years later. Writing about what he spoke about with James Joyce those nights they both were three sheets to the wind. EH worried about JJ’s drinking. Go figure. JJ was magic with words, but EH had a hell of a time understanding him. The feast is served to eternity on a text after considerable consternation and cognitive contortions by the chef. In the eating comes the celebration while the author feeds worms as all great writers do eventually.

That’s what Walt Whitman says, but he likely stole it from Shakespeare.

*****

The idea that any textual representation of human experience could be a potential “moveable feast” occurred to me in late 1989. I was selected to work on the teacher team charged with developing secure reading tests according to specifications from the California English Language Arts Advisory Committee made up of educators. My understanding of the significance of ELAAC in the moment was pitifully thin. ELAAC discussed and finalized the vision for English Language Arts assessments. Teacher teams, directed by teacher leaders and university professors, wrote the reading and writing tests. Without the power vested in ELAAC, I might as well have been innovating happily in my own classroom.

It was immediately clear that everyone engaged in the CLAS reading test project understood the vision. There was little debate, though there was much joyous hair-splitting. The teacher team would make manifest a test of reading without resort to multiple-choice items. A statewide writing assessment system (CAP) had been functioning since 1986. The new reading test would merge with CAP to assess both writing and reading across California.

*****

As the months passed the development team wrote reading prompts, field tested them in their own classrooms, reflected and reported back to everyone, often with written commentary, banked the ideas that seemed promising, and eventually constructed a collection of high-quality prompts to field test on a large scale. A powerful and highly useful rubric emerged from iterations of small-group analyses of field test responses. I began to think about separate test forms the team generated and field test responses from children over the next few months based on grade-appropriate literary passages as “feasts.”

Passages were carefully selected for their qualities. Assessment activities opened doors to a variety of ways for students to respond, including annotations linked to texts and reflective questions posed following the reading. Test activities scaffolded reading work to build one on the other to propel the reader cognitively but not substantively—and to optimize leaving evidence behind. The text of the test became a feast; the texts of the reader in response became another feast.

This process of teacher-driven research and development of the reading test mirrored the process used to create the CAP Writing Assessment system.

*****

CAP work product was the result of a tightly focused architecture for a districtwide or statewide writing assessment system. Cooper and Brenneman (1990) summarized this architecture as follows:

What most intrigued me about this perspective on writing assessment was the complexity buried within its simplicity. It was admittedly pragmatic, addressing a definite need for information to improve instruction while not controlling nor automating it. The vagueness of the broad categories, as Cooper pointed out, introduces a sloppiness which permitted the Common Core State Standards to emphasize persuasive writing at the cost of limiting and formularizing writing instruction.

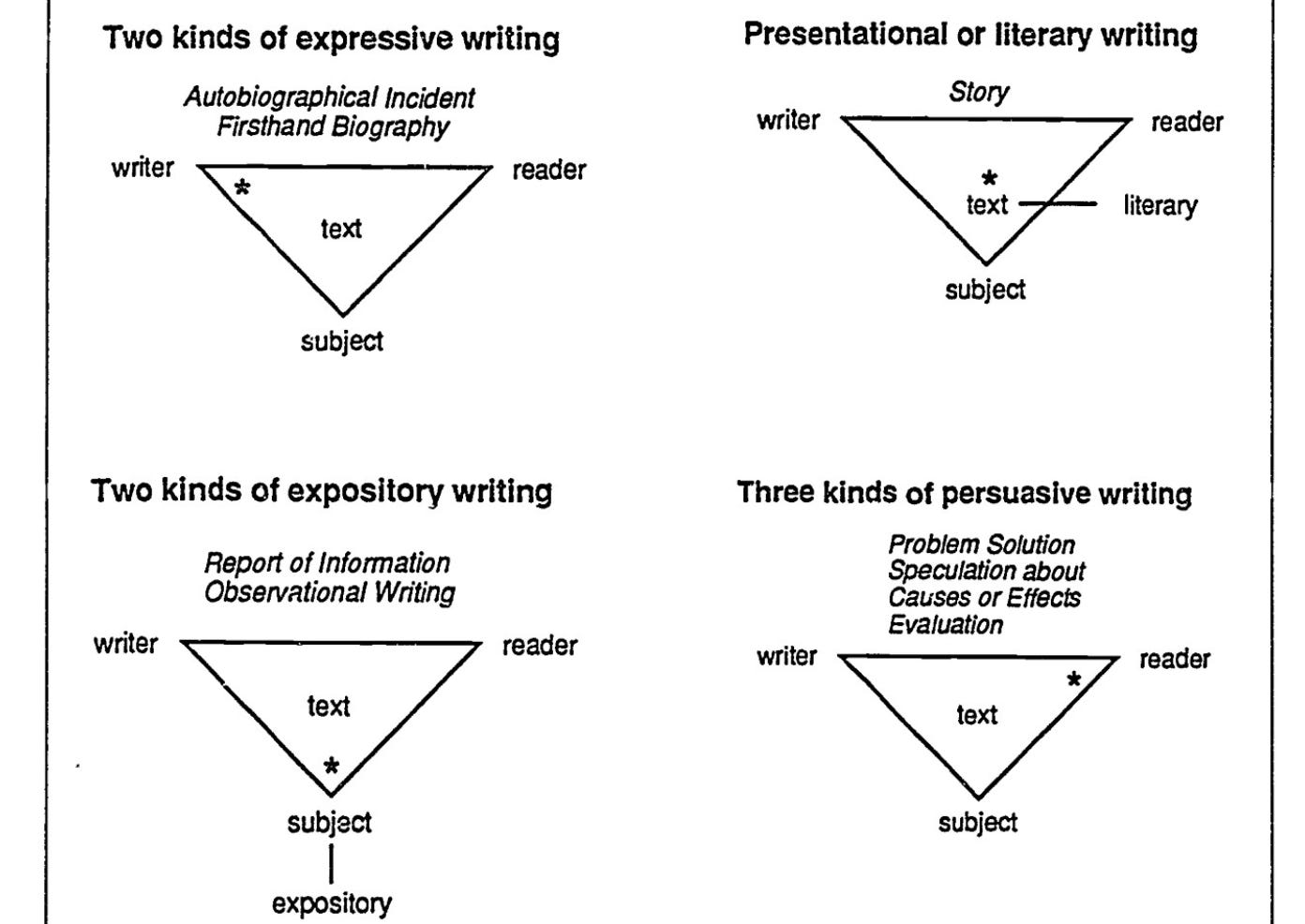

Cooper prepared diagrams using Kinneavy’s Triangle. I came to call the T in the center of the triangle the “moveable T.” I still use the phrase as if it’s common usage. Cooper’s rationale for the CAP writing types becomes transparent here:

Three continuums illustrate different modes of the writing: a) the shift from personal experience to external subject matter; b) the progression from self-expression to reader-oriented communication; and c) the spectrum text to text. By exploring these continuums, teachers can help students understand how various forms of writing balance the writer's voice, subject matter, audience needs, and textual elements, encouraging a more nuanced approach to both reading and writing across different genres and purposes.

The writer-to-subject continuum could support a menu of writing projects taught one at a time across several weeks. Narrating and reflecting on personal or collective experiences can generate motivation and interest to build community while introducing students to stable and durable routines in a writing workshop setting. Connecting personal insights to broader topics or issues, including controversial issues, can flourish in writing projects wherein community has been fostered and the teacher is skilled. Integrating personal perspectives with factual information can involve narration and explanation with a more precise and sharp cognitive edge regarding factuality. Researching and presenting information objectively can invoke multimedia presentations and collaborattions.

The writer-to-reader continuum starts with purely personal writing. Many teachers who use quick writes as an individual brainstorming technique to get juices flowing foster a classroom culture that privileges privacy with no pressure or expectation of sharing. Just reminding students of this right to think privately on paper is usually enough. Shifting to the right, write about a hobby or interest, explaining why it's meaningful while also providing information that might interest others. Craft an open letter about a social issue, balancing personal perspective with arguments designed to persuade others. Create a guide explaining how to do something, focusing on clear, reader-friendly instructions. Write a review of a product or service, combining personal experience with information useful for potential consumers. Develop a frequently asked questions page for a fictional (or real) organization, anticipating and addressing potential user queries.

The fact-to-imagination aesthetic text continuum could legitimately receive attention in the writing classroom, it seems to me, since literature is a staple reading assignment in the English Language Arts. Given a dominant focus on creating an aesthetically elegant text, literary writing is not always fictional. Here is a take at marking off points on a continuum: a) literary journalism, i.e., factual reporting with a strong emphasis on narrative techniques and stylistic prose (e.g., works by Joan Didion); b) creative nonfiction, i.e., true stories told using literary devices and techniques; c) biographical story or novel, i.e., a fictionalized account of a real person's life, blending historical fact with imagined dialogues and scenes; d) historical fiction, i.e., fictional stories set in a meticulously researched historical context; e) speculative fiction, i.e., imaginative works based on plausible scientific or social developments; h) high fantasy, i.e., completely imagined worlds with their own internal logic and rules. This list doesn’t mention drama or poetry.

*****

Given the vagueness of the Common Core’s map of the universe of discourse, there is plenty of curricular space for innovations in reading and writing instruction in English Language Arts classrooms. Narrative, expository, and persuasive writing as a catchall may work fine in theory, but as an organizer for writing instruction, it is a recipe for chaos—that is, unless the five paragraph essay on persuasive steroids is the only acceptable assignment. Writing well is challenging. Writing across the universe builds capacity. Local departments and/or district curriculum coordinators may find wiggle room to try something else.